Bitcoin Part 1.0: Reading the Whitepaper

This is the third article in a series where my goal is to understand the blockchain, NFTS, and the related technologies.

In this article, I will use the pronouns “he/him” to represent Satoshi Nakamoto, not because I am assuming his/her/their gender, but because it will make things simpler. I would also note that although Satoshi uses “we” all throughout the paper, notably in science and math, it’s quite common for academic papers to say “we” even though it was written by just one author.

Reading the Bitcoin whitepaper

I think the right and honest way to introduce Bitcoin is by going back to the paper that started it all: the Bitcoin whitepaper. Now that we have the prerequisites covered, we can dive into this paper.

1. Introduction

In the introduction to the Bitcoin whitepaper, Satoshi Nakamoto describes the problem of having to trust intermediaries in financial transactions. He also says says how a centralized authority must settle/mediate disputes, and the more transactions there are, the more disputes there will be, and therefore the higher the operating costs will be. These middlemen are obviously not doing charity work and working for free, so if operating cost goes up, well then they must carry the extra cost onto their users via extra fees, or they will (as Satoshi writes) increase the minimum transaction amount. Then he describes the problem of reversible transactions, where a fraudulent buyer could initiate a transaction, receive the goods, and then initiate a refund to get the money back, leaving the seller without the goods or the payment (1).

His solution:

“a peer-to-peer distributed timestamp server to generate computational proof of the chronological order of transactions. The system is secure as long as honest nodes collectively control more CPU power than any cooperating group of attacker nodes”.

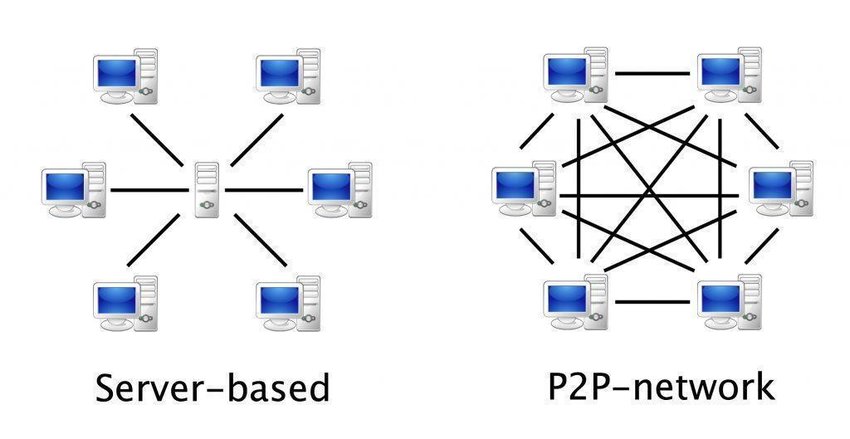

The idea to remember here is that there is no central authority maintaining the system. It’s a system by the users, for the users.

And regarding the merchant/buyer situation, he writes “Transactions that are computationally impractical to reverse would protect sellers from fraud, and routine escrow mechanisms could easily be implemented to protect buyers”. I doubt he mentions anything more about setting up these “routine escrow mechanisms”, but let’s read on. The point here is that once something is on the blokchain, it’s permanent.

2. Transactions

So how will transactions work on this network?

“We define an electronic coin as a chain of digital signatures.”

I gave an introduction to digital signatures in the previous article, but for the whole story on that, check note (2).

But briefly, if I “digitally sign” something, that’s a proof that I own the private key, which no one else is going to have. So everyone in the world can see a message that has my digital signature and be able to confirm that I signed it.

“Each owner transfers the coin to the next by digitally signing a hash of the previous transaction and the public key of the next owner and adding these to the end of the coin.”

This means that when a bitcoin transaction takes place, the current owner of the bitcoin (i.e. the person who holds the private key to access it) digitally signs a hash of the previous transaction and the public key of the next owner. This digital signature serves as proof that the current owner is indeed authorized to transfer ownership of the coin.

As we can see here, a transaction is nothing more than 3 numbers: the new owners public key, the hash of the previous block, and the old owners signature. As an example, let’s follow the path of 1 bitcoin as Ann first sends it to Bob, and then Bob sends that bitcoin to Charlie.

Ann wants to send Bob a bitcoin, so within the transaction data she will include Bob’s public key (some number), the hash of the previous transaction (let’s assume we have that) (also some number), and then she will concatenate Bob’s public key with the hash, and encrypt that using her private key, thus signing it. Now that bitcoin belongs to Bob.

Now Bob wants to send the bitcoin to Charlie. So Bob gets

- Charlie’s public key, then he takes

- the hash of the previous number (basically concatenating the 3 numbers from the “Ann->Bob” transaction, and taking its hash), and finally

- Bob signs the transaction. So now we have the “Bob->Charlie” transaction pointing back to the “Ann->Bob” transaction via the hash. On top of that, the the fact that Bob signed this transaction with his private key can be decrypted with his public key, which can be found by going to the previous transaction (the “Ann->Bob” transaction).

Thus, we get a “chain of digital signatures” from all the owners of the coin(s) being transferred (one new owner at a time). And this chain of owners is permanent, so if a hack or illegal activity has occurred and some of that Bitcoin ends up in your possession, law enforcement may be able to trace the transactions and seize the Bitcoin as part of their investigation (3).

So far, there is nothing revolutionary. Using digital signature is old news.

“The problem of course is the payee can’t verify that one of the owners did not double-spend the coin. A common solution is to introduce a trusted central authority, or mint, that checks every transaction for double spending.”

This is something we want to obviously avoid. And the fact that Bitcoin solved this problem is one of the many reasons why it is so revolutionary (4).

I don’t know your thoughts on this double-spending problem, but I was a bit confused at first. How hard can it be to keep track of who owns what? Why not just give me my private key (my wallet), and have a pointer pointing from my wallet to the Bitcoin that I own. We learn the concept of pointers early on in our C/C++ class. What’s the problem?

Well, the problem is that I’m still thinking inside the box. This approach would require a trusted central authority to maintain a database of all Bitcoin ownership records, and this would defeat the purpose of Bitcoin’s decentralized and trustless nature. The truth is that hindsight is 20/20; the blockchain’s concept may seem obvious now, but in reality it is revolutionary. Let’s read on to see Satoshi’s solution.

“The only way to confirm the absence of a transaction is to be aware of all transactions. In the mint based model, the mint was aware of all transactions and decided which arrived first. To accomplish this without a trusted party, transactions must be publicly announced, and we need a system for participants to agree on a single history of the order in which they were received. The payee needs proof that at the time of each transaction, the majority of nodes agreed it was the first received. “

An agreed upon chronological order of all transactions is the solution to the double-spending problem.

3. Timestamp server

As it turns out, the root of the solution to this problem has already been written in 1991.

In this short section, Satoshi talks about data being “timestamped” and somehow publishing it somewhere so that everyone can have access to it (as a generic example, he writes “newspaper”).

As it turns out, “timestamping” is not a new concept. In 1991, Stuart Haber & Scott Stornetta (5) published a paper called “How to time-stamp a digital document”. Here are the first two sentences of that paper:

“The prospect of a world in which all text, audio, picture, and video documents are in digital form on easily modifiable media raises the issue of how to certify when a document was created or last changed. The problem is to time-stamp the data, not the medium.”

So by now you may be wondering: what is timestamping?

I’ll answer that question by answering what Stuart Haber and Scott Stornetta were trying to answer back in 1991: “how do we create immutable record?”, in other words, “how do we create digital records (of anything) that intrinsically can prove to anyone that they are in fact the original records (that they haven’t been altered)?” And remember, all this without the help of an central authority to tell us “trust me”. Because, digitally, it is easy to copy, alter, and paste. It’s like asking, how do I know for sure that I have the original Mona Lisa that Leonardo da Vinci himself painted? I’ll leave some notes about how to came to think about it (6).

To solve this, what they did was literally “time-stamp” data: they combined the time (which is universally agreed upon and it is also a one-way street, i.e. always moving forward and changing) with a particular piece of content, to create something new, that is unique and condesed that into a (unique) hash.

In section “7. Application” of their paper, they write:

“[…] timestamp a log of documents rather than each document individually. For example, each corporate document created in a day could be hashed, and the hash value added to the company’s daily log of documents. Then, at the end of the business day, the log alone could be submitted for time-stamping. This would eliminate the expense of time-stamping each document individually, while still making it possible to detect tampering with each document; we could also determine whether any documents had been destroyed altogether.”

And Satoshi also writes the following in this section:

Each timestamp includes the previous timestamp in its hash, forming a chain, with each additional timestamp reinforcing the ones before it.

Let’s look closer at what this diagram is saying.

Let’s take 3 items which, for whatever reason, we need to prove that they were created at a particular date/time. Let’s now group these items together and call that a “block”. We will now take the hash of the previous block (don’t forget that all “items” are just bits in a computer, so you can take a hash of anything digital) and concatenate the items of the current block, and take the hash of all that. That will be summarized in the “hash” box. Then you simply repeat, and form a chain of blocks and hashes. So let’s say we collect all the logs of a business throughout the day, and at the end of the day, we combine them into a block, take yesterday’s hash, and append it to today’s items, and then calculate the hash of all that. Everyday we will do the same thing, and so if today is Friday, and someone tries to go back and change even one bit from file from Monday’s logs, then this will change the hash value of that block, and affect every hash which was calculated on the following days, since they all depend on Monday’s hash. It is thanks to the link between a hash and every following hash, causing a ripple effect and making it clear that someone changed something from Monday’s documents.

In order to remove the centralized authority which takes care of storing this chain of hashes (TSS: “Time-Stamping Server”), Stuart Haber and Scott Stornetta write:

[…] several members of the client pool must time-stamp the hash. The members are chosen by means of a pseudorandom generator that uses the hash of the document itself as seed. This makes it infeasible to choose deliberately which clients should and should not time-stamp a given hash. The second method could be implemented without the need for a centralized TSS at all.

That’s what they left Satoshi with, so it is up to him to put a practical implementation to all this.

Notes:

1

On a personal note, it’s interesting that Satoshi is so adamant about the fact that the buyer can screw the seller over, and that reversibility of transactions is terrible. We can easily argue against this and say that someone can accidentally send Bitcoin to the wrong address, and would need to reverse the transaction. Or if I purchase a product or service, send the money, but the product or service does not meet my expectations, in which case I’d get screwed over.

2

In the second article of the series I explained how a digital signature can be made using your private key… sort of. To be honest, I didn’t tell the whole story. I just said how you can use your private key to sign a message by encrypting that message, and anyone with your public key can unencrypt the message to see that you encrypted it, proving that it went through you. Read on to learn how signing actually happens.

Assymetric encryption has its pros and cons. One big “con” is that is that it’s a slow process, compared to its “symmetric counterpart (which we didn’t discuss about, but it doesn’t matter); the mathematical algorithms are more computationally complex and the keys themselves are also more lengthy. Given these two facts, encrypting an entire message is costly. If only there was a way to instead work with a smaller representation of the data (like a fingerprint of the message), then we’d be able to encrypt that instead. Well, there is a way to convert any amount of data into a fixed, relatively small representation of that data, and it’s called hashing.

Ann writes a message. She then runs her message through a hashing algorithm (SHA256 in the case of Bitcoin). The result will be some 256-bit (64 hexadecimal characters, which is what I showed in the previous article) called a hash, or digest. Now Ann is going to encrypt (with her private key) that message digest, and the result of that will be the encrypted digest. This encrypted digest is the signature for this particular message; it will be appended to the message and sent off to Bob. So now Bob will use Ann’s public key to verify the signature. More specifically, Bob will unencrypt the encrypted message digest, and the result will be the message digest. Then he will independently generate the hash of the message itself, and if his calculated hash is the same as the hash which he unencrypted from Ann, then he knows two things: the message has not been tampered with since it has been signed by Ann (known as “integrity”), and Ann was the one to sign the message (property of “authentication”).

It is important to see how a digital signature isn’t like a signature we write by hand. A signature by hand is going to be the same (or at least very similar) every time, while a digital signature will change every time, as long as the messages are different.

3

Of course they would have to follow proper legal procedures and obtain a warrant or court order to seize any assets, including Bitcoin. And if you acquired the Bitcoin through legitimate means and were not aware of any illegal activity, you may have legal options to contest the seizure. That being said, if you went into some underground marketplace to acquire these Bitcoins at a price lower than the market price, well then you were likely in the receiving end of Bitcoin “dumping”, i.e. those Bitcoins were likely acquired illegally and the person is just trying to get rid of them quickly. That’s why it’s always best to buy and sell Bitcoin through legitimate, regulated exchanges.

4

Other reasons why it’s revolutionary are: decentralization (maintained by a global community of users), transparency (anyone with an internet connection can access it and inspect it), immutability (this is important if you want to be trustworthy), limited supply (different from any other currency like fiat currency or commodity like gold), and it is programmable (open-source software that can be used for other more complex applications requiring blockchain tech).

5

The question these two were trying to solve was “how do we create immutable record?”, in other words, “how do we create digital records (of anything) that intrinsically can prove to anyone that they are the original records (that they haven’t been altered)?”

6

At first, they thought that this problem had no solution. As they were writing their proof that you cannot remove the need to trust someone, they ended up seeing that this proof can be looked at in the other direction, and could be made to work. In Scott Stornetta’s words, “if two people are trying to prove something, but they collude, then you need a third person to look over their shoulder. But what if they draw that (third) person in the collusion, well then you need a fourth person, and so on and so forth. As a result, we were trying to prove the absurdity of the act that you had to eventually trust someone. Phrashing it that way, I realized that the collusion would have to involve everyone in the world. And then I realized if you turn that upside down and created a system of interlinked documents with essentially everyone as a witness, then you had in fact solved the problem.