Bitcoin Part 1.1: Continuing Reading the Whitepaper

This is the fourth article in a series where my goal is to understand the blockchain, NFTS, and the related technologies.

4. Proof-of-Work

In the previous section, we saw how one block’s identity is determined by the previous block, and the previous block’s identity is determined by the block before it, so on and so forth. All blocks are linked, and a change in a block from the past will cause an error in the hash values of all the future blocks. Ok good.

Now what if I am someone with malicious intentions. Going back to the “corporate” example, where a company will publish all its log files at the end of a day, and combine those into a block and do the same thing for the rest of the workweek. If it is Friday, and I want to go back to Monday’s records and change something there. If we are using timestamping, as we discussed, if I change something on Monday, then the hash values of Tuesday’s, Wednesday’s, Thursday’s and Friday’s blocks will change, and the whole system will break. So what I can do, before anyone has the time to check that I broke the system, is I can recalculate the hash values of all the blocks following Monday. Because in reality, calculating a hash value of something takes less than a second.

So to make this harder, Satoshi introduces the concept of “proof-of-work”. The main idea here is that in order to add/modify a block, it cannot be easy. It must be hard. To make a link between two blocks should not be as simple as running a hash function once. So if I change something on Monday, therefore breaking all the links going up to Friday, it will be hard for me to recalculate everything in a way that it works mathematically. It will be hard for me to go to other people, and tell them “I swear, this is the right sequence of blocks, not that one”.

And this is a problem that arises with decentralization. Because if a central authority was running the show, then they’d just have one chain. Only they have access to it, and so there is one truth. However, when dealing with people all around the world, anyone can come forth and say “this person owes me this much, look at this chain!”.

So let’s say we have a transaction Tx. A transaction will replace what we called “items” in section 3. Also, inside the block, we’re going to have the hash of the previous block, and a “nonce” (“Number used ONCE”).

“The proof-of-work involves scanning for a value that when hashed, such as with SHA-256, the hash begins with a [certain] number of zero bits. The average work required is exponential in the number of zero bits required and can be verified by executing a single hash.

We concatenante all the transaction with the hash of the previous block, and with the nonce. We then take the hash value of that. The proof-of-work system asks us to find the value of the nonce such that the resulting hash will start with, say, ten 0’s. This is not easy to do; out of the 64 hexadecimal characters, the first 10 must all be 0’s. Once you find a nonce which will yield that result, then you have PROVEN that you have done the WORK. Furthermore, others can verify that you have done the work very easily; all they have to do is take the nonce that you found, plug it in, calculate the resulting hash, and if they get a hash where the first 10 characters are all 0’s, then they have verified your work. (1)

For our timestamp network, we implement the proof-of-work by incrementing a nonce in the block until a value is found that gives the block’s hash the required zero bits. Once the CPU effort has been expended to make it satisfy the proof-of-work, the block cannot be changed without redoing the work. As later blocks are chained after it, the work to change the block would include redoing all the blocks after it.

Essentially, “bitcoin mining devices” are just calculating hashes all day long (simply changing the nonce each time), and once they get a winning hash, they announce it. The first to find a correct nonce wins! It’s not too different from playing the lottery if you think about it. And just like if you buy more tickets, your odds of winning increase, a node/miner (person participating in the blockchain) has more chances of finding the right nonce if he/she has more CPU power. As Satoshi writes, “Proof-of-work is essentially one-CPU-one-vote”.

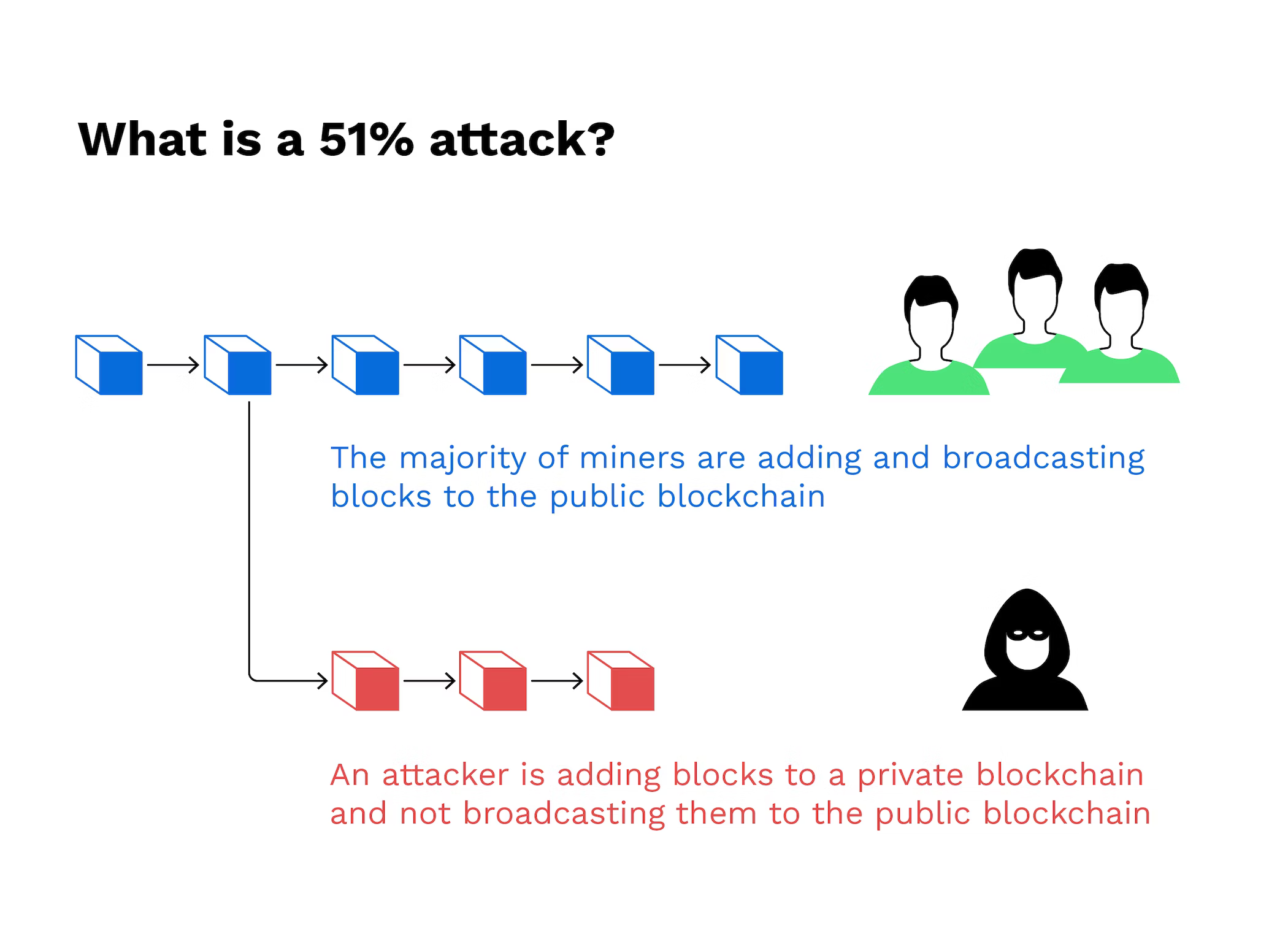

The majority decision is represented by the longest chain, which has the greatest proof-of-work effort invested in it. If a majority of CPU power is controlled by honest nodes, the honest chain will grow the fastest and outpace any competing chains. To modify a past block, an attacker would have to redo the proof-of-work of the block and all blocks after it and then catch up with and surpass the work of the honest nodes.

Let’s say there is a group of malevolent miners (nodes) (people who are trying to find a right nonce) who control more than 51% of the total computing power (a.k.a. the hash rate) of the network. Then what this group can do is create an alternative chain of blocks (with a different transaction history), mine those faster than the rest of the “good” miners are mining their legitimate chain, and then once the fake chain is longer than the legitimate chain, everyone on the network will adopt the longer chain. This is how the proof-of-work system works: the chain which has the most work put into it will be the one that the nodes agree is the legitimate chain. This is called the 51% attack, and it is considered to be a serious threat to the security and integrity of the Bitcoin network, but it is also increasingly difficult and expensive to carry out as the network grows and more participants join.

5. Network

Let’s not talk about this “P2P network”. There are clear steps that the network follows when Ann wants to send Bob some bitcoin.

- To reiterate, Ann will broadcast to every node that she is connected with, and all those nodes will share the transaction with all the nodes that they are connected with, so on and so forth until every node on the network is up to date.

- Nodes are constantly on the lookout for transactions, because they need to fill up their block so that they can start looking for a corresponding nonce.

- Each node works on finding the nonce (by trying nonces and calculating the hash).

- Once a node finds a nonce for its block, it will broadcast the block to other nodes.

- “Nodes accept the block only if all transactions in it are valid and not already spent”. The details on this one are trickier (2), but essentially, all other nodes will validate the block, and if valid…

- They will add this block to their version of the blockchain and continue the process, collecting transactions from nodes and building a block to hopefully eventually add to the chain.

“Nodes always consider the longest chain to be the correct one and will keep working on extending it. If two nodes broadcast different versions of the next block simultaneously, some nodes may receive one or the other first. In that case, they work on the first one they received, but save the other branch in case it becomes longer.”.

Note that as a node on the network, just because a block has been broadcasted and added to the blockchain, doesn’t mean that it is trustworthy. Instead, you should wait for several new blocks to be added on top of it. If, after a while, you haven’t heard of any longer chains of blocks which doesn’t include the block in question, well then you can trust that this block is part of the same chain that every other node is working on.

6. Incentive

Now, why would anyone put up with running a node? Why should I spend money to buy computer hardware, or an ASIC (Application-Specific Integrated Circuit) miner, and spend money on electricity, in order to validate blocks on the blockchain? As it turns out, there is an incentive.

When you add a block to the “legitimate” chain, you are rewarded with bitcoin. The first transaction of every block is not “Ann paying Bob for guitar lessons”, no. The first transaction noted on every block in the blockchain has always and will always (until we run out of bitcoins to mine) be a gift from the Bitcoin network to the node which added that block to the blockchain. Once we reach the cap of 21 million bitcoins, then the nodes running the system will be gifted in another form: transaction fees.

Today, this gift awarded to the miner of a block is 6.25 bitcoins. 4 years ago it was 12.5 btc, 4 years before that it was 25 btc, and 4 years before that it was 50 btc. Sometime in 2024, the reward will be 3.125 btc. The dates are fuzzy because the halving occurs after 210’000 blocks have been added to the blockchain, and that occurs approximately every 4 years.

So the further we go in time, yes, there are more nodes on the network, all competing to mine the next block, but also the reward you get for doing the work is less and less (that of course depends on the price of 1 bitcoin, so not completely true). The idea, from my understanding, is to limit the introduction of new coins, so that as demand increases, supply doesn’t increase as fast, and this leads to the price increase of every bitcoin.

7. Reclaiming Disk Space

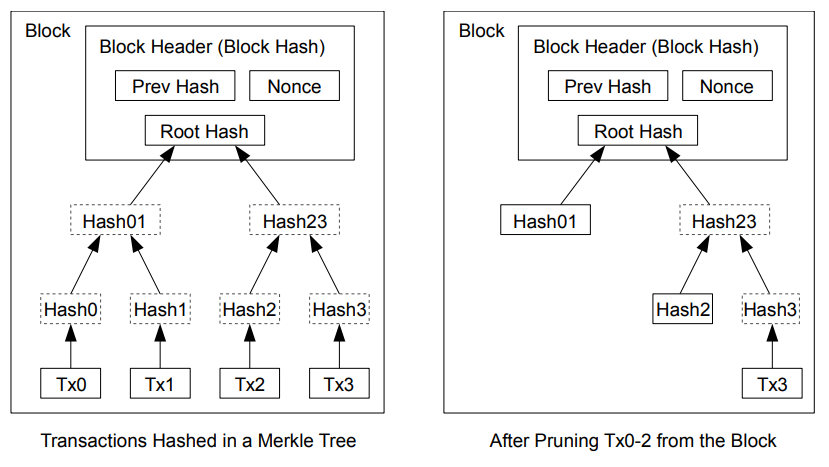

The idea here is that if we have a coin that’s moving from one owner to the next, we do not need to store every single transactions’s hash. What matters at the end is who owns the coin. If Ann pays Bob 1 bitcoin, and then a week later Bob pays Charlie that same bitcoin, well in order to make sure the system is intact and everyone has access to the coins that they own, we don’t need to know that Ann used to own that coin last week… at least not directly. This information can be deducted, if need be, thanks to the Merkel tree (a.k.a. “hash tree”).

A tree has a root node (the “Merkle root”), and this root node will be a hash representing all of the transactions in a block. There is no need for nodes on the network to store every transaction anymore. And by combining all transaction in this manner, we save disk space for every node. And all this while still maintaining our tamper-proof property (if I go back a few blocks and change one transaction, the “root hash” will be different, and my block will be invalidated, causing a ripple effect onto the following blocks).

To hit the point home, in the image above, on the left, we have a block with 4 transactions. The Merkle tree is formed by concatenating the hashes of 2 subsequent transactions, and then repeating that with the hashes created, going up in the tree, until there is nothing left to combine; at that point, all the transactions are combined and summarized by the root hash.

The image on the right shows what happens if will never need to reference transactions 0 1 and 2 ever again, so we remove them and store their hashes instead. The hashes of Tx0 and Tx1 can be condensed together to save further space. All in all, instead of storing 4 transactions, we are now storing 2 hashes and 1 transaction (Tx3); that’s 3 items instead of four transactions. It doesn’t seem like a big deal when dealing with 4 transactions, but in reality, a block on the Bitcoin blockchain today holds, on average, 2000 transactions. So while 25% of 4 items is only 1, 25% of 2000 items is 500.

Here is what Vitalik Buterin had to say in the Ethereum whitepaper about the use of Merke Trees in Bitcoin:

“The Merkle tree protocol is arguably essential to long-term sustainability. A “full node” in the Bitcoin network, one that stores and processes the entirety of every block, takes up about 15 GB of disk space in the Bitcoin network as of April 2014, and is growing by over a gigabyte per month. Currently, this is viable for some desktop computers and not phones, and later on in the future only businesses and hobbyists will be able to participate.”.

8. Simplified Payment Verification

The concept of the Merkle Tree ties in very closely with SPV because they both talk about efficiency. Section 7 showed us that nodes don’t need to store all the data on all the previous blocks in the bloclchain. This section talks about how if you are a node on the network, you can participate in the network without knowing all the details of past transactions. This is useful for systems which are low on resources, such as a smartphone.

“A user only needs to keep a copy of the block headers of the longest proof-of-work chain, which he can get by querying network nodes until he’s convinced he has the longest chain […]. He can’t check the transaction for himself, but by linking it to a place in the chain, he can see that a network node has accepted it, and blocks added after it further confirm the network has accepted it.”

Basically, the blockchain network can now consist of

- nodes which have the entirety of the blockchain, with every single transaction detail saved,

- nodes which contain some amount of detail (keeping only the relevant transactions using the concept of Merkle Trees), and

- “Light” nodes, which only keep a copy of the block headers, without any of the details about the transactions which any of the blocks contain. They can however ask (“query”) other (more “knowledgeable”) nodes on the system if a certain transaction Tx has occurred.

9. Combining and Splitting Value

Not going to lie, I was happy to encounter this chapter. Because up until now, I have only been talking about moving one entire bitcoin from Ann to Bob and then moving that exact same bitcoin from Bob to Charlie. In reality, it is more likely that Bob will receive 1.28523 BTC from Ann, and that he will then have to send 0.762304 BTC to Charlie.

This section shows that one transaction Tx can contain many inputs and will usually contain two outputs: the first output will be the receiver of the transaction, and the second output will be change (if any) sent back to the sender. Let’s look at an example.

Ann has 0.5 BTC, and wants to send Bob 0.3 BTC. This transaction will break up Ann’s currency into two separate outputs: The 0.3 BTC owed to Bob, and the 0.2 BTC left behind. This 0.2 BTC will be sent back to Ann. Hence why there are two outputs most of the time.

Today, we have the concept of “Unspent Transaction Output”, or UTXO.

“A UTXO is essentially the unused part of a transaction. Every time a cryptocurrency transaction takes place, existing inputs are deleted and new outputs are created. Any outputs that aren’t immediately spent become a UTXO that’s tied to the sender in the transaction.” (source)

To be honest, the details (with the public/private keys, how to check who has access to what, etc.) are kind of complicated, but even Satoshi doesn’t get into it in the whitepaper so I won’t either.

10. Privacy

Here, Satoshi talks about pseudonymity.

“The public can see that someone is sending an amount to someone else, but without information linking the transaction to anyone.”

So your identity is separate from your bitcoin wallet (mostly not the case today)(3).

11. Calculations

Here, Satoshi simulates an attack on the Bitcoin network. He considers the case where the attacker has less than 50% of the CPU power of the network, and proves that the attacker will have a very (extremely) hard time trying to hack the network; the attacker basically has to be extremely lucky with finding the nonces (as explained in section 4) and creating a separate chain of blocks from the legitimate chain, and adding the blocks onto that chain faster than the legitimate chain is growing.

Actually, maybe this part isn’t so clear, so let me dive deeper into an example.

Attack on the Blockchain example

Let’s say I pay for a Lamborghini with bitcoin. The dealership tells me “hold on, we want to wait a bit to make sure this transaction is valid, is accepted by everyone and exists on the blockchain”.

That’s a fair argument, we wait an hour, they’re convinced, I get my Lambo and head home.

Now, I didn’t actually want to pay for the Lambo. In order to break the Bitcoin system, and get my money back (and disappear the Lambo), I have to go back to the block BEFORE the one which contains my lambo purchase, and start a new chain from that point on. The first block that I will add to my “local” blockchain will be exactly the same as the block which contained my transaction with the dealership, except I will remove that transaction. Basically, in my version of reality, this transaction never occurred, i.e. I never paid the dealership anything.

However, now that I changed something in the block, the hash will likely not start with the required number of 0’s (section 4 topic). So I broke the nonce/data combination by changing the data, and so now I need to “mine” the block and find a new nonce which will yield a block hash starting with the required number of 0’s. Furthermore, by changing one block, I now invalidated every block which followed it, because they all depend on past blocks’ hashes. Now all of their hashes don’t start with the required number of 0’s, and so I will have to “re-mine” all of them and try to catch up with the legitimate blockchain (it’s me against all the honest nodes of the world, and they have a head start). I basically have to get super lucky to find the right nonces for every block, until my chain is longer than the legitimate chain, at which point I announce to other nodes that I have a chain with more “proof-of-work” (i.e. it is longer than everyone else’s), and the nodes on the network will accept my chain as the legitimate one and start to build on top of it.

If I succeed, the dealership will see tomorrow that they do not have access to the funds which I paid them. They panick, go online to check the blockchain history to verify their transaction with me, and see that it was never recorded and basically never existed… even though yesterday they saw that it was on there.

In reality, this will not be happening. The chances are extremely low and the safety of the network grows exponentially as a function of the number of blocks ahead of the block which an attacker wants to change.

In the snapshot above, q is the percentage of hash power which the attacker has compared to the rest of the system. So in this example, the attaker has 10% of all the hash power. z is the number of blocks in front of the block being attacked. So if there are no blocks in front of the block being attacked, i.e. there is no node in the system that has confirmed what is in the block, well then the probability of attacking it is 100% (the attacker’s created block is as valid as the parallel block which is legitimate, but which also doesn’t have any node confirm it yet). This is why you should do what the lambo dealership did, and wait for the network nodes to confirm the transaction to cement it in the blockchain.

However, things start to turn for the worse once the legitimate block gets another block on top of it (z = 1), i.e. the network have confirmed it and built on top of it. Now the attacker has a 20% chance of catching up. So on and so forth with the other numbers. And from my understanding, the industry standard is to wait for 6 blocks (that’s 1 hour of waiting) in order to be confident that the transaction in question is permanent and will not be reversed.

The example below this one in the whitepaper shows that if the attacker has 30% of the cpu power, then his chances are much better (5 blocks deep, the attacker has 17% of a successful attack).

However, all of this goes out the window if the attacker somehow manages to control at least 51% of the network’s computing power. In which case Bitcoin becomes pointless and worthless.

12. Conclusion

“Nodes can leave and rejoin the network at will, accepting the proof-of-work chain as proof of what happened while they were gone. They vote with their CPU power, expressing their acceptance of valid blocks by working on extending them and rejecting invalid blocks by refusing to work on them. Any needed rules and incentives can be enforced with this consensus mechanism.”

Looks to me like a beautiful design.

Notes:

1

Historically, CPU power has largely followed Moore’s law, which predicts that the number of transistors on a microchip doubles approximately every two years, resulting in a significant increase in processing power. Processing power has historically followed Moore’s law, which says that the number of transistors on a microchip doubles approximately every two years, resulting in a significant increase in processing power. Although it is unlikely that the trend will continue for long (due to physical limitations), the idea is that processor speed is always increasing.

So if 10 years ago the network required you to find a hash with five 0’s, with today’s computational power, five 0’s is a joke. The number of 0’s keeps increasing to keep it difficult to find the winning hash. In fact, the system is set up so that the number of leading 0’s is equivalent to whatever will make someone find the right nonce in about 10 minutes. So it depends on the “hash rate” of the network. If a block was generated in 8 minutes one time, then the next block will increase in difficulty. The more miners there are, the more 0’s there will be, and so the harder it gets. Same thing for faster CPU power.

2

How do we know if a block is valid? In other words, how do we know that every transaction Tx in the block have not already been put in some block before? Because if transaction Tx has already happened before, then having it occur again would mean we’re “double-spending”, and we don’t want that.

In order to solve this, we must know that every transaction has its own unique ID. The transaction’s ID contains the ID of the block that it’s in, and the transaction number within that block (so is it Tx #1, 2, 50, etc). What we can do is search every block in the block chain that came before to see if this particular transaction can be found somewhere. If not, then this transaction is an original and we can move on.

In computer science, this is called an O(n) computation. The concept is hard to explain, but basically, we have to check every single block, and that is not the most efficient way of doing it. Instead, we can reduce this to O(log(n)) using the following method:

If you’re a node, whenever you add a block to the chain, you had to have validate each transaction within that block. And so when you go through them, you can store them inside your RAM (for example). In your database, you can store the transaction IDs in ascending order. And no you have a sorted list of past transactions, and you have a new transaction which you want to check if it is in that list. So now you can run your favorite search algorithm.

Previously, we did what’s known as “linear search”, which is searching through every item. But now that we have a sorted list, we can do what’s called a “binary search”. In binary search, the list is divided in half at each step and the search continues in the half that may contain the desired item. This reduces the number of elements to search by half at each step, making this approach much faster than “linear search”.

3

This paper was written in 2008. Back then, it was simpler to jump in and participate in the network through mining bitcoin. At the time, mining was relatively easy and required only a small amount of computing power. Regulated exchanges such as Coinbase and Binance didn’t exist back then.

In order to fund our Bitcoin wallets today, we must send our money from our bank to the exchange, and then through the exchange we can put money in our digital wallet. Gone are the days where you could just join the Bitcoin network with a latptop, and earn bitcoin. So this section is a bit obsolete.